Projects Development Manager

This story is taken from a recorded interview conducted in April 2016 and is transcribed with very little editing to preserve the details. The photographs were captured between April 2016 and February 2017.

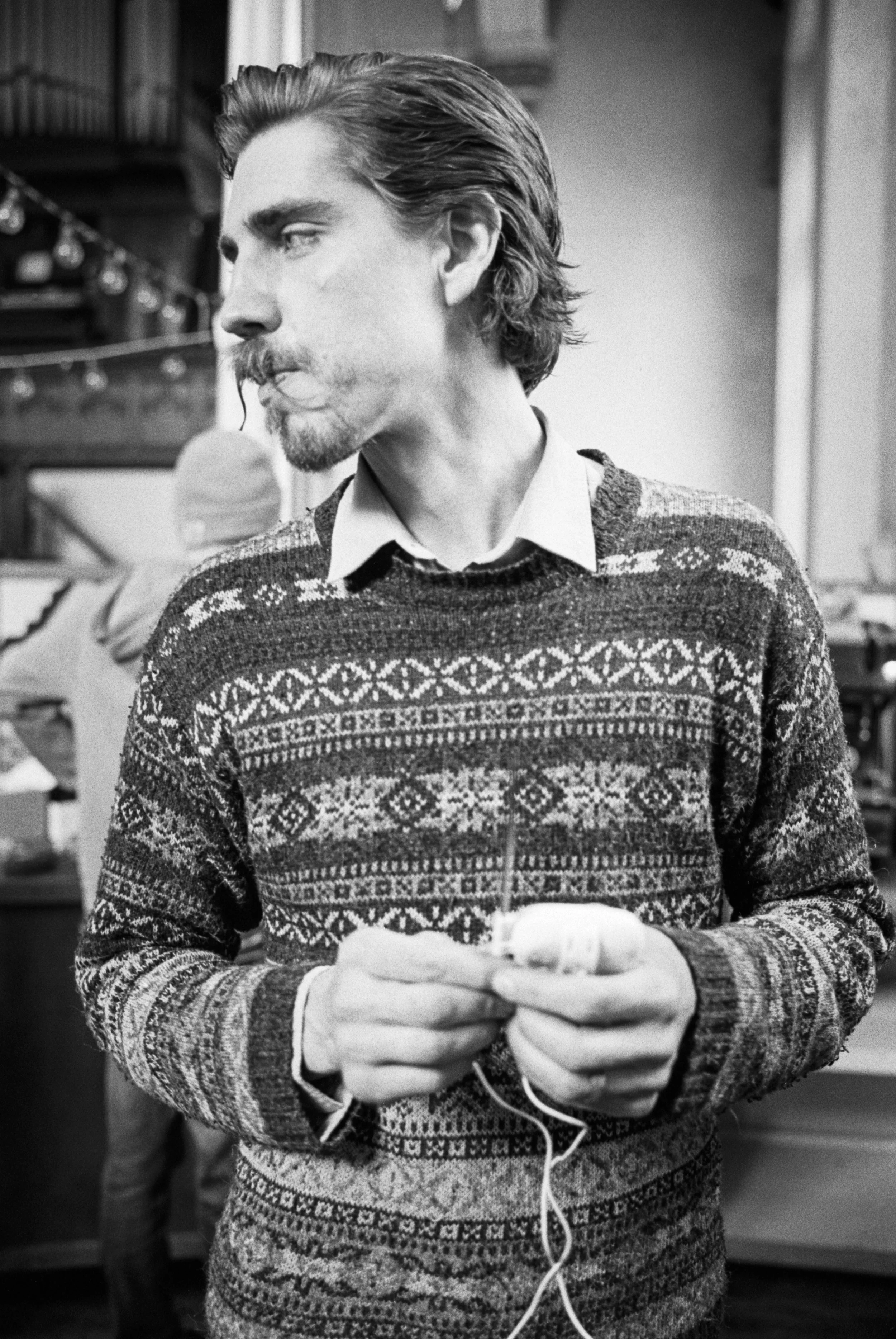

My name is Ben, Benjamin Paul Szobody

It's a perversion; my name comes from a Hungarian great-grandfather, who went to the US to work on the railroads. But he was illiterate, so they misspelt his name at Ellis Island, so it is a permutation of what would have been Szabadi, meaning from the town of Szabad in Hungary.

I live in a terraced house in Hollingdean in Brighton, UK, with six children and a wife and a lovely housemate. These aren't conditions in which I imagined living, I still own a house in America with a quarter of an acre and plenty of yards and deck space, we're not urban people, but we've come to embrace the close quarters and the meaningfulness of living in the community partly due to financial pressures and societal pressures and rent pressures. The most important thing about home for me is it's where Michelle (my wife) is. We've always had an attitude that we really could do anything as long as we're together. So, I don't feel geographically like any place on earth is deeply home to me, Brighton is more that than anywhere else I've lived, but I've only been here three years. Home is where Michelle is, for me. And we tend not to feel settled unless we're together.

Michelle is the intellectual genius behind a lot of my verbose spoutings, Michelle is an extremely quiet and well read and creative thinking person, where I'm all hard charging get it doneness, Michelle, just like my mother is deeply satisfied having children and pouring herself into them and Michelle always wanted to run away to England, and I'm convinced I joke that she married me only to get her out of Greenville South Carolina, but that's not true. We do everything together; she's a part of our farmers market, she comes out to the farm, she educates our children, alongside me, but mostly her. Michelle is my team mate in a profound sense.

Childhood was regimented in the sense that we were very clearly made to know how we should behave.

How would I describe growing up? I would have had a highly unusual upbringing. In a huge family, that was not at all what people expect huge families to be. So, I was the oldest of 12 children, although there were never 12 while I was still at home, cos I was the oldest, but we were always a very large family. The kind of family that would walk into a fine restaurant and make everyone blanch in terror, only at the end of the meal to be the recipient of many congratulations for having such well-behaved children that potentially would have terrified everyone, but actually ended up impressing everyone. That's how my dad raised his kids, he loved having a large family, my mother loved having children, and so it was large but peaceful. Everyone had their roles, everyone felt very confident and nurtured and not at all bouncing of the walls of chaos you'd think of a large family.

Childhood was regimented in the sense that we were very clearly made to know how we should behave. If we could behave in that way, then the ultimate freedom was ours. In some ways I would still reflect that philosophy in my own child-rearing. As a result, I was an extremely independently minded person, I had a lawn mowing business by the time I was 12, making good money by the time was 14, my father was regularly borrowing large sums of cash off of me.

I set my business up because I wanted to do that at 12. We lived in a small town where two very large estate homes needed young boys to mow the lawn. It was the kind of deep south town where they let a 12-year-old push a mower around and give him $20 to do it. So that was the beginnings of it, and I seized the opportunity and off we went.

Someone's an art teacher, someone's a literature teacher, and you can get quite a good education.

For about half of my childhood, my parents would have defined work as something that puts bread on the table. That would have been the era when my father was an architect, quite a good one, but someone that needed to pay bills and raise a large family. He grappled, my father did, with a change of career mid-life, giving up a certain identity, and embracing one that he might not have imagined, and that was becoming a minister and eventually moving to Chad to minister to very poor people indeed. So, later in my childhood, I suspect my father would have defined work as something more akin to answering the calling that's in your life and not worrying about the details because the details would have seemed absurd and impossible, particularly with so many children. And then watching and seeing what happens. And that's proven extremely fruitful for my dad's life, and he would say that in spite of malaria, and the violence and the other risks of living in an extremely poor country, in the middle of nowhere for a decade, he couldn't be happier, he's right where he needs to be. In many ways, I've reflected a lot on my dad and how he managed those transitions in my own life.

School was all done at home, this would have been a part of my parent's unusual child rearing philosophy. Home education is much more developed in the US, we lived in South Carolina, where education is still left up to the states. The federal government doesn't intervene or set standards for the most part. Therefore, the quality of education can vary dramatically from state to state, and in South Carolina, we were ranked 50th in the country for education. So if you cared about education, you either had money and sent your child to private school, or you didn't, and you home schooled. As a result, there is a very developed home school culture there, where you can buy quality curriculum and enter co-ops with people. Someone's an art teacher, someone's a literature teacher, and you can get quite a good education.

So I was homeschooled, along with all 11 of my other siblings. It was quite a structured environment when I was a child, which means that I probably focused really intensely on school work for 2-4 hours a day. If I got my school work done, it was done, and I was free to go. That was another reason probably why I developed a business at such a young age; I had time on my hands, I could work all afternoon if I wanted, and make a lot of money. In that sense it was very self-driven, I certainly had a teacher grading my material and looking over my shoulder, with a lot of classical forms of education, a lot of reading literature. Science was my favourite, in particular, astronomy. I had high ambitions of being an astronomer, if not a space traveller. I was very much a memoriser of constellations and a watcher of the night sky, it was one of my hobbies.

When I went to University it was initially terrifying, I was 15 years old.

I graduated from high school at the age of 15, and I was three years early. That was a bit of a fluke, but that further added to my independence, my ability to run a business and ultimately my ability to go to university at a very young age.

When I went to University it was initially terrifying, I was 15 years old, we lived in Arizona at the time, I was moving across the entire country back to South Carolina, and the reason I did that is because my father said 'Look, I am aware of a religious University with a lot of rules around behaviour and I would imagine, even though I don't agree with all those things, that that would be a safe place for a 15-year-old to go to University'. So he said, either you keep working for a couple more years and make a bunch of money and go where you want, or you go to this University in South Carolina, and you can go now, and I said, I'll go now.

I was quite tall, I probably could have passed for 18, I lived in the dorm, I had roommates to whom I lied about my age, and I was initially terrified for that reason, how does one get through history of Civilisation, in a classroom setting, rigorous exams. Fortunately, I had done a lot of rigorous exams; I had done standardised tests which all school children are required to do. I very quickly learned that I could work the system, in that public education and systematised education was a system that one could navigate if one were politically savvy.

Although I think I did quite well academically, part of doing well, means, learning what effort is required for the A, and no more, as opposed to loving what you are learning and absorbing as much as possible. That's what I mean by working the system, I just mean what students do in school, they get the top marks possible for minimum of effort. I very quickly learnt I was good at that and I was fine at that, and I ended up doing quite well, and finished with honours, and graduated at the age of 19.

I went straight into journalism, I had majored in print journalism, and it's quite unusual for someone coming from university to go straight into a good sized newspaper, but as a result of an internship that's what I did. I became a business journalist pretty quickly and spent nearly fourteen years at a medium-sized newspaper in South Carolina where I did investigative work, politics, business and lots of digging and diving and that sort of stuff.

'This is highly unusual, but if any kid can pull this off, it's this one'.

Ultimately going from homeschooling to university to a job was all one arc in my mind of independent-mindedness and sprinting after something I thought I could do. I think my parents let me go to university aged 15 because they saw how extremely independent minded I was and thought well 'This is highly unusual, but if any kid can pull this off, it's this one'. That's not to say anything about my talents or my smarts, it's just to say I was a right stubborn bull headed person, so as a result, for much of my life I've developed probably an extreme sense that I'm always the youngest in the room, I've always got to prove myself and I will. If anything's got me in trouble, it's that. It's the inability to take a back seat and let the work come to you; it's that insistence that if I don't make it happen, then it won't. Which is an odd thing, because in one sense there was a lot of capability there, which people call maturity, but there are probably a lot of immaturities that say, ‘I've always got to show you that I can do it’.

One story that might indicate that immaturity that still existed despite having progressed quite a ways at a young age is a journalistic thing where my talents and abilities were there, but I occasionally would rashly charge in a direction that was ill advised. I very quickly climbed the ranks of the newspaper. I was covering state government for a while, I was covering a now notorious governor of South Carolina, you might have heard of him. He was the one who disappeared to Argentina with a mistress while he was in office, which became something of a red letter scandal nationwide in the US. He and his staff were quite forceful behind the scenes with how they wanted their message to get across, and I, on the one hand, was promoted to the level of being able to deal with and interview the Governor of South Carolina, on the other hand, I almost got fired on a couple of occasions, where I spoke an ill-advised word. I twisted their arms too far, I was a bit too opinionated, it was an email, it was documented, they turned it against me in a classic sort of political move to try and get a journalist fired who they saw as critical of their administration. So there were times like that where I was brutally reminded by my bosses and others that you are not all that you think you are and that was a 21-year-old mistake.

I love writing, I love the pressure of journalistic writing, so why did I leave? I still see myself as a writer in terms of identity, but the journalism business is cracking apart, and the revenue has disappeared. Gone are the days when you could pay someone minimum wage to type 3 lines, you know, 'Car for sale, call this number' and charge obscene amounts of money for it. These things happen for free now on the internet. So the funding to send people to Iraq and buy them bodyguards to do deep reporting or to pay me to spend months digging through records to expose wrongdoing in state government is no longer there. So increasingly I found myself being assigned pretty inane things to do when I wanted to do really impactful things for society. Furthermore, we always wanted to jump overseas, either the UK or France, but those jobs were drying up as well as a result, there just weren't any more foreign correspondent gigs anymore. So I got tired of waiting for the career path abroad to open up, and there were some bizarre events that led to us doing an MA in Brighton.

We realised there were needs out our back doors that were unheeded and untended.

I would have struggled giving up my identity as a journalist and a writer, I went to school for that, developed that as an identity. I spent a lot of years on that. But ultimately I wanted to have more of an impact on society. In our private lives we ended up doing quite a lot with homeless people in our area with local food, community gardens, involving vulnerable people, that sort of thing. But that was private life stuff, that was community stuff. I think all 14 years of journalism, I didn't want to be in South Carolina. I wanted to be abroad, so for the first few years that was an intense enough desire for my wife Michelle and I that we sort of ignored our neighbours, and didn't pay attention to where we lived and couldn't have cared less because we were thinking about moving elsewhere.

And there's something that occurs when you are forced to be somewhere I think, and you realise the need to be rooted whether or not you love the place that you are in. I love what the Scottish land reformer Alastair McIntosh says. He told me one time when I was filming him, that rootedness is the most transferable of skills, there's a paradox there. So lo and behold after a number of years, we were in a circle of friends and people who all were a bit restless and wanted to move on in life in terms of geographic location. But we realised there were needs out our back doors that were unheeded and untended, particularly in a conservative political region such as that (SC). It just wasn't the kind of place like Brighton, where the homeless are on people's radar.

So I came to find out that there were people in my neighbourhood that were knocking on doors asking for cash to mow someone's lawn and that sort of thing that had barely triggered my attention but was right in front of me. Equally I had a next door neighbour that had grown quite old and frail but had a massive garden plot behind our house and she'd offered it to us. She couldn't bear to see it overrun with weeds and as we began to do this we realised we couldn't do it alone, so we began to invite our friends and people we knew, and that became the community garden.

‘I know a guy in Brighton, we have a free afternoon, let's go meet him.’

It was almost like I was insensitive to some of the social needs around us, and they were very quiet sort of subtle needs to begin with, and the longer we were forced to stay in this place, the more I began to tune into them. And when I tuned into them I realised to my chagrin, that there were things to do right in front of me, social things, things around vulnerable people in our own backyard. That was such a humbling thing to realise, that I had been so focused on escaping that I couldn't see the needs right in front of me. In a very ironic twist I think it was that understanding, that willingness to get rooted in a place I didn't like, the willingness to look for the vulnerabilities right in front of me, that ended up linking to our current work in Brighton. More than anything, that was the seed of it. Journalism didn't bring me here, and the career didn't take me all the places I thought it would. Instead, it was a bit of having my eyes opened to the needs that were in front of me.

In a sense, moving to Brighton and doing an MA was an attempt not to leave media and journalism but thinking it might be time. I had made a visit to Brighton; it was really a fluke. I was visiting some social projects in London, Monaco and France. I was beginning to think outside my normal career path in terms of what might bring me to the UK. We just did not feel culturally suited to the American South, particularly once we started to pay attention to vulnerable people. There was a need there, but culturally it was an uphill battle, very much God, guns, Republicans and Nascar country to stereotype a little bit, maybe that's not fair.

In London, the fellow I was travelling with said ‘I know a guy in Brighton, we have a free afternoon, let's go meet him.’ It was Dave Steell who is the Minister of One Church. I didn't know what I was getting into, but when I saw Brighton and I thought about homelessness, and I thought about local food systems which are things we'd gotten into. That's the sense in which I mean that this stuff we'd began to dabble in, this stuff that started to soften our hearts a little bit, became the linkage really.

So I thought, wow, what a town that is.

I still thought well, it's almost too cool of town, surely I'm not called to go there. But we went home, we consulted a bunch of our friends, we consulted our community, and they seemed to say really clearly that they thought it was our gig, that I'd been applying for all these journalism jobs over the years and nothing works, this could really suit me. I didn't really understand how that could be true, but my wife actually got online, I'd always wanted to do a masters degree, she said ‘hey, Brighton a town with two university's, lets see what they got’, and lo and behold there was a new MA starting up at Sussex University called Media for International Development. With my parents living in Chad at this point, I was very into International development and what they were doing and being conscious of these things.

So what a thing, I applied, and got accepted right away, but the Visa situation being what it is in the UK, we needed nearly $75,000 in the bank upfront to get a student visa to spend one year studying in Brighton. That seems crazy, but I have a number of children, and that inflated the price a little bit. We had zero at the time, we had saved a good bit but because we pay for our medicine in America, and I have a son with some serious digestive issues we had just emptied the bank account of about $10,000 to pay for some of his stuff. I thought, how are we going to get $75,000?

Long story short, I got a tax return worth about $10,000. Then a fellow at a church we were going to walked up to me and said, 'why do you keep taking these trips to the UK'? And I said it might sound crazy, but there's this town Brighton, and it seems suited to what we're into at the moment, and I got accepted on this MA program which is right up my ally, imagine that. He got a bunch of guys together in our church, some were business leaders, and they said, ‘we'd been really thinking about investing our money creatively, not just supporting people in a traditional sense, have $50,000’, and they wrote us a cheque. I was beyond astonished, beyond floored.

At that point our other friend saw the handwriting on the wall and went 'right this is going to happen isn't it', and we started having friends and neighbours writing us cheques, which is the most terrifying and most humbling thing imaginable. I even had a next-door neighbour who's a bit of a character who I love but hated us some days and loves us others I think, and he wrote us $1,000 and said 'look I was gonna put new siding on my house, I'll wait a year, put this in your send the hippies to Brighton fund'. The last thing I wanted to do, being a headstrong careerist, was to be in the position of taking money from people and then being on the hook for how I used it in another country. I would have much rather forged my own way, but in two months flat we went from zero to $80,000, and we didn't ask anyone for a dime, that's the shock of it.

We sold all our stuff, sold our car, rented out the house and off we went.

In the end, that's how it happened. We shockingly were able to apply for a visa, meet the financial requirements and move to Brighton within a few months. We sold all our stuff, sold our car, rented out the house and off we went. Everyone said you can't move to England with 6 children, and I said, watch me, this is what we want to do. So I ended up here doing an MA in Brighton, and because we had this money to live on for a year, which was a legal requirement, I had a free year to spend and we said, let's not waste the year, we'd like to stay, don't know if we're going to be able to stay, so let's absolutely not waste it. We literally volunteered and said yes to anything that moved. I was doing an MA, but after the pressures of journalism, it felt like a holiday, it felt like, I can write a few essays and attend some lectures, and I've still got 5 days a week to spend, so that's how we approached it.

It's a shocking story; people can't believe it when I tell them. I think it was meant to be. I think it's one of those things where people sometimes squint their eyes at us and go 'are you missionaries', and you go, no, and they go 'do you have some secret business you are working on, are you entrepreneurs", and you go no. All we know is I think we are doing what we've always done, we are living in the way we've always tried to live, but in a place that's more suited to those particular urges and dreams. That's it.

It's astonishing that in spite of hating the place where we lived, we were put flat on our faces really, in humility, and taught that the career wasn't going to do it, my pathways wasn't going to do it. You know, as someone that does believe in God, I would say, God was teaching me a lesson that said 'I've got better plans, and actually I can put it together, and actually once you learn how to be rooted and to love the place you're in, then fine, here we go, I'll open an amazing pathway to another place'. And it's well beyond what I could have planned.

This is the moment I had to come to grips with ‘am I still a writer or not, am I still a journalist or not’?

So the MA was half about media and filmmaking, and half about development and social change. You could say that I went in from the media sector and came out in the development sector really. As a result of one of the volunteer projects we did during that Masters degree, we ended up starting a farmers market, a very unusual one in a neighbourhood, not on the high street. Partly designed to embed ourselves in the community, to develop local food systems which we really cared about, to sell produce from a farm project which we were volunteering for, which we really cared about. But to build community in a place and to use food, and using quality local food it was where it was justifiably needed. As volunteers we started it as a bit of a lark, it was embraced by the community, became quite a thing, generated a nice little revenue stream, and it was on One Church property, at their other building on Florence Road in Brighton. That farmers market ultimately led to a job developing social projects for the organisation. They saw the success of the market and we started to imagine what else we could do.

This is the moment I had to come to grips with ‘am I still a writer or not, am I still a journalist or not’? On the one hand, I would say it was very much a struggle giving up journalism as a career, on the other hand, it was very close to the dream job.

I can remember sitting in our community garden in South Carolina, and a photographer friend of mine, a dear friend, was just staring at the landscape of tomatoes and Chinese noodle beans and saying 'some day, this is all going to come together', and I said what do you mean, and he said 'the teaching and the food and coffee and the community and the writing, and the farming, it's all going to come together in an amazing job'. And I said, ha, I've never heard of a job like that before.

And when One Church said 'why don't you run a farmers market, help manage an organic farm project where we help vulnerable people and help us build a community space in central Brighton where we might develop a coffee program to train young people', it pretty much ticks every box, except for the writing box. So that's the sense in which I say, it was very nearly the dream job offer, and I had to answer that question, am I writer anymore, or can I give that up.

'This is a different type of community of people'.

The organisation I work for is called One Church; it's a bit unconventional, it's a bit Brighton. One Church is a church, and the people of faith meet as a church in one of the buildings. One Church is also larger than a Church; One Church is a registered charity and a community of people, not all of whom are religious, who are oriented around social projects aimed at the most vulnerable people in Brighton. So that includes everything from homeless night shelters to unemployed young people and getting them into jobs, to low-income families facing food poverty issues to seniors in social isolation. These are all things that we do in this building, and as a charity that are not evangelistic things, they are things that we believe we are being called to do.

A church that's welcoming and has the ability to absorb any kind of person no matter what they believe in the moment, it's an astonishing thing, not a club with a barrier of entry that says you must tick these boxes before you walk in the door. That was the kind of thing that made me think I could do this there. I baulked a little bit at the thought of working for a church or a charity, but these are the things that wore me down, the things that said 'this is a different type of community of people'.

My main job consists of three pieces, I run a farmers market where you can buy quality local produce, I manage a building in central Brighton where we do loads of stuff for vulnerable people, and I support a farm project where we grow food, alongside people that need to get out of the city and who need help. The farm is hands on; I'm not there often enough to manage or run things. I am leading the horticultural side of it, where we plot what we are going to grow for the year, how much can we grow, where do we sell it and how much can we get for it to support the project. Yet again, a growing hobby that involves vulnerable people being part of my job, how good can it get really.

The whole reason I was attracted here was the vision of making a profound difference in the city.

I really struggle to describe this building (One Church in the centre of Brighton), we were just toying with language earlier this week. In managing this building, you're talking about a big two story century old Baptist church that is no longer a church in the way people think of church, it's a collaborative space, it's a community project. Some of the projects in the building One Church run include a homeless shelter through the winter months on Wednesday evenings. They include a project called Chomp that tries to deal with food poverty during the school holidays when people miss their free school meals. They include a project called know my neighbour, that is attempting to get at the root of social isolation by encouraging people to do the simplest of things, which is to be aware of who their neighbour is.

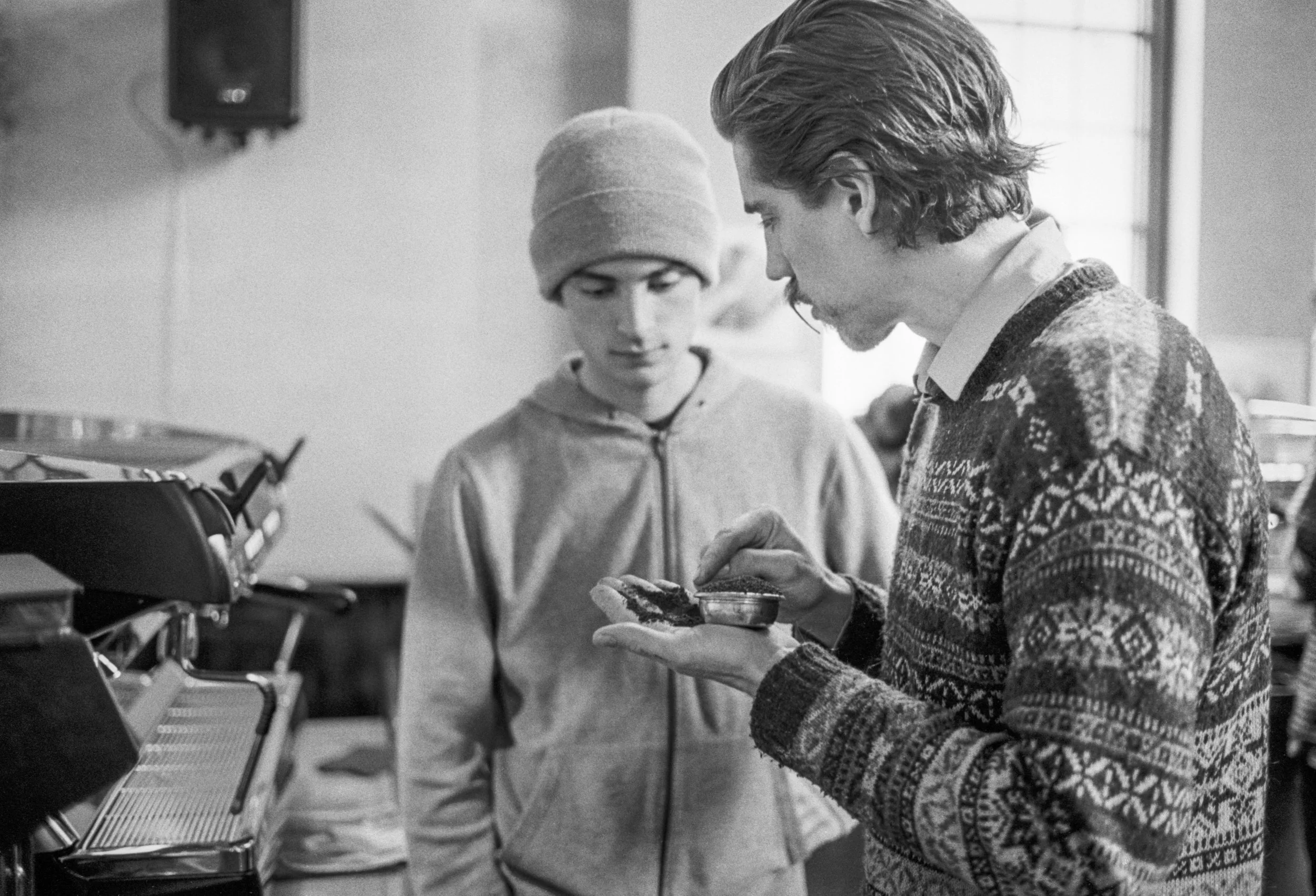

We also run a barista training project, and that's one of mine that I manage and run. We offer unemployed young people top shelf barista training. There's an industry out there that is booming, the speciality coffee industry that the top end of the coffee industry and they are desperate for skilled labour, so why not connect the two. We have found a way to run an apprenticeship as well as several other training schemes where young people can have the door opened to them, that would otherwise remain closed, and businesses can have one of their main costs and needs met with trained staff. So those are examples of projects that One Church runs in this building. There are also other projects that outside charities run.

On my day off I try to publish Longberry magazine, which again is that attempt to look at the world of coffee, which I'm very nerdy about and care a lot about, with a serious journalistic lens, and it's not something anyone else is doing. In partnership with James Hoffmann, who's a well-known coffee personality in London, who owns Square Mile coffee, we publish a magazine that attempts to look at climate change, the politics in coffee producing countries that are sometimes quite perverse and propped up by coffee. We try to look at absurd trade relationships that are lopsided in our favour; we look at silly cultural things that are happening around coffee at the consumer end, it's an attempt to do some interesting and serious writing about topic that we love. I still wonder if I have a problem and identity crisis to do with being a journalist, so I publish this magazine, partly just to keep a foot in that world. There’s no money in it, it’s not a business, just a belief in writing and ideas really.

One of the central struggles of my life is to balance the day to day sprinting around which ultimately is what sharing a building requires, with that grand vision. The whole reason I was attracted here was the vision of making a profound difference in the city. It's not so different from the journalistic impulse, which is 'I want to change society for the better'. I might be able to do that as an investigative journalist, or I might be able to do that as a hub in Brighton that flips the paradigm on its head as often as possible in favour of vulnerable people. If we are a building where a certain type of music is known to be played, if we are a building where food waste is being harnessed and being put to use for the poor, if we are a place where the most brilliant ideas can go to be nourished and grown, if we're a centre where social projects find their feet and brilliant food and drink is knitting people together, that's the vision. When you look at how big this building is, when you look at what's possible, then you think we're not half-way there yet.

How much do I value my job, well, it's very nearly my dream job?

And it's very nearly a dream job that I wouldn't have known to wish for. I think ultimately you want a job that takes more out of you than you knew you had but doesn't leave you drained, leaves you more nourished than you were at the beginning. And at the moment, that's almost precisely how I would describe this job.

How does society value what we do, well that's an interesting question? I think I would have never even contemplated working in the charity sector in the US, partly because there's a very emaciated charity sector in the US. And therefore it simply wasn't a thing anyone aspired to do. Here in Brighton, I'm astonished by the percentage of my friends who happen to work in the charity or social enterprise or CIC sector. But does society value those things, I'm not sure it does. But I don't come to the job as a person who's accustomed to working in the charity sector. And so I think I partly come to the job with an intent of proving value.

It might be amazing to drink the perfect flat white, but for the most part, there is only a certain class of people doing that.

Maybe I'm still trying to prove myself, but why are food and drink such a core part of what we do? People chuckle about this and ask me that, gosh, is that all you do, food stuff? People might derisively dismiss you as a foody, given the fact that you run a quality farmers market and do high-end coffee, that would be an easy label to slap on somebody and dismiss them. But the subversive part comes in when you bring vulnerable people into the mix. Again, you are turning the paradigm on its head, in their favour for their benefit. So there might be a lot of posh coffee jobs out there, but unemployed young people aren't getting them, now they are.

It might be amazing to drink the perfect flat white, but for the most part, there is only a certain class of people doing that. I'd like to do a cafe in the ground floor of this new senior housing complex across the street, where some of the best coffee in Brighton is being made, where people are most socially isolated and is reversing that trend. If this doesn't sound too bizarre, we want to use food and drink, some the most basic human elements that people crave, to create linkages and to show value where people would have least expected it.

I can remember my first Sunday in One Church and seeing that there was rubbish sticking out of the loft, and things weren't all in order and I got a big smile on my face, because I realised this is right where I wanna be because the energy isn't in making ourselves slick, it is out there serving the needs. So you could say that part of that subversiveness is refusing to do the corporate marketing thing and to make sure everyone knows about, but it's just to get on with it. And then when people discover you there often becomes a profound attachment from people going 'you won't believe what I found', so I don't know that that's a strategy, but that's how we've ended up operating.

If anything's missing from my work, I think it's probably the ability to shift gears and slow down and think about the future.

I've just come off a three-week holiday, which maybe has never happened in my life, and although I fantasised about lots of reflective time and big picture thinking, I found that either I was in bed till noon in a fit of profound laziness, or was going stir crazy and had to do something, and so I sand my floor till two in the morning. Both of which are extremes, which just says that I have trouble shifting gears and slowing down. But once I do, you see what it is that's important to see; you see what it is you should be doing, you are able to ascertain what's worth your time and what's not. And it's just so important, so in a shared building we can feel pulled in many directions, it's very important therefore that someone has a vision, and someone has a destination in mind, and I must constantly get better at being that person or one of those people, because I don't think it comes naturally.

I think one of the most difficult things in life for me is dealing with people's disapproval, particularly if I esteem them. That's the flipside of the coin of being driven and independent, I can sprint along until I find out that someone who I truly admire is upset, and that has a crippling effect on me, and I should probably care less what people think, but if I'm really honest, I think the emotional paralysis and anxiety that occurs when I'm convinced someone is upset with me is a major struggle with my life. It doesn't happen often. It's partly due to the fact that I stew over things, I think it probably makes me politically savvy, probably makes me able to negotiate lots of relationships well, but when I fail, then it can be devastating to me, partly because of what it does to human relationships.